A Cold Hardy Smaller Fan Palm

INTRODUCTION

Trachycarpus is a genus of palms that are solitary, single trunk plants with fan leaves. They are referred to as Windmill Palms or Chusan Palms. Interestingly, the term “Windmill Palm” is used to describe the most common species of the group (Trachycarpus fortunei) as well as the group in general. They typically have fibrous material on their trunks and are small to medium in size. Many species have remarkable cold tolerance. All are native to various countries in Asia. They have become quite popular with people who want a cold tolerant palms that doesn’t take up too much room. There are quite a few types of Trachycarpus. One species of this genus, Trachycarpus fortunei, is specifically called the Chinese Windmill Palm. Trachycarpus are used ornamentally around the world, especially in areas where more tropical species won’t survive. Trachycarpus consists of about eight to ten species with perhaps more varieties or species coming in the future. Their native distribution spreads from India east through Myanmar, northern Thailand and into China. This list of species has expanded in the past decade because field work being done by those with a keen interest in Trachycarpus.

This article will review the genus Trachycarpus, discuss its characteristics that are descriptive of the genus, make comments on culture and usage of these palms in the garden, and finally describe some of the most commonly seen or interesting species within this group.

THE GENUS TRACHYCARPUS AND ITS CHARACTERISTICS

GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF GENUS

The genus Trachycarpus consists of approximately ten species. All species are from Asia, spreading from India through Myanmar and Thailand into China. This is a fan palm that has differences in leaf color, crown size, trunk diameter and height. These differences account for the different species. Most species come from mountainous areas where significant cold weather is seen. Leaves are palmate with deeply divided leaflets on most species. Often there is a glaucous color to the underside of the leaves. Sometimes even the tops of the leaves can be a bit blue in color. Petioles reach out form the trunks with relatively small leaves. Trunks on most are narrow and overall this is considered to be a cold hardy, smaller fan palm.

TRUNK

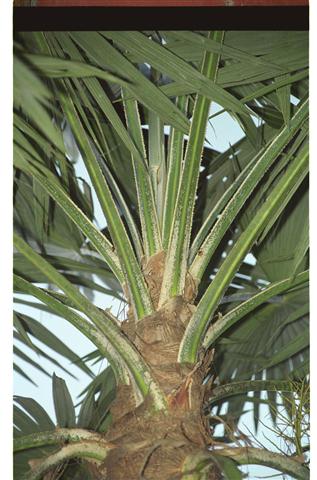

All species within this genus have a single trunk. They do not sucker. Heights of these trunks range from almost nonexistent trunk to forty feet or more. Trunks tend to be rather thin, usually less than 12 inches in diameter. A remarkable characteristic of the genus is the production of thick fibrous material or hairs that cover the trunk, especially the upper trunk. This soft material covers circumferentially a trunk that is much thinner than first observation would suggest. This fibrous material can fall off with age, finally showing the thinner woody trunk interior to the fibrous material. When a specimen tree is very old, it is not unusual at the base to see the thinner hard trunk. Or, if one so desires, he could manually remove this fibrous material to show the woody trunk. An interesting thing is that sometimes one sees the bottom twelve inches or so of the fibers haphazardly pulled off in a messy way. This is often the result of scratching animals like skunks that are looking for insects hiding in the hairy trunk.

It is very rare to see a “petticoat” of old leaves on a Trachycarpus, but it can happen. The term “petticoat” describes literally hundreds of old dead leaves hanging down on the upper trunk and continuing down the stem. One commonly sees this on Washingtonia and some other genera. One might see some dead leaves hanging down, but it’s rare to see the classical petticoat. I have posted one photo below taken by M. Gibbons that does in fact show a petticoat on a palm in Nepal.

Regarding the fibrous trunks, you can see with the photos below that the trunks are hairy and fibrous along most of their course. If a thinner woody trunk is seen, it is at the lower portion of the trunk. This fiber material is rather haphazard in its design. It is not as nicely woven or attached as one sees with Coccothrinax species. The last photo is a containerized Trachycarpus wagnerianus. Note the long fibrous hairs emanating from the trunk, almost reminiscent of the trunk of Coccothrinax crinita, The Old Man Palm.

LEAVES

The leaves of Trachycarpus are fan shaped or “palmate” and tend to be rather flat or in a single plane. On some species or plants, the ends of the leaflets will hang downwards toward the ground. The individual leaflets or segments can be divided part way toward the center or almost all the way to the center of the leaf. The first two pictures below show how the segments go almost to the point of attachment of the petiole. Overall leaf size ranges from small to medium, depending on the species. An average leaf width would be three to four feet. T. wagnerianus tend to have stiff, small leaves. Trachycarpus fortunei have larger leaves with the distal ends of the segments often flexing downward. The color on the dorsal side of the leaf is deep green. The underside of the Trachycarpus leaves many times will show a bluish discoloration. This is from a waxy substance produced by the leaf. This can be a quite prominent blue on some species such as Trachycarpus princeps. The stems (petioles) are either smooth or minimally armed and range from one to about four feet in length. The length of these stems is greater when a plant has been grown in filtered light compared to full, hot sun.

CROWNS

The crowns of leaves of Trachycarpus tend to be compact, spherical in shape, and not overly large. Plants grown in filtered light or shade have longer petioles and the crown of leaves is more open and spreading. Plants grown in intense light tend to be more compact and smaller. Older leaves turnbrown and hang downwards adjacent to the trunk. These can accumulate if one doesn’t prune the tree, but in time these just fall to the ground. One of the differences between the species is the “openness” of the crown. Also, some species have rather stiff leaves while others are softer and tend to have drooping at the ends of the segments

SEEDS AND FLOWERS

Flowers are branched and appear from the stem among the leaves. Trachycarpus are dioecious trees. There are males and females. This means that, to produce viable seeds, one must have pollen from a male flower make its way to the female blossoms. The flowers appear within the crown of leaves and are are typically yellow or tan in color. They are branched blossoms and when pollinated produce small, black fruited seeds. The appearance of the cleaned seeds varies within the group of species, but no species has large seeds. Immature seeds are green. One knows that the seeds are mature when they turn black and fall off the flower easily.

CULTURE AND GROWTH OF TRACHYCARPUS

COLD TOLERANCE

Many species of Trachycarpus are native to high mountainous areas in Asia where they experience very cold weather. Because of this, some have remarkable cold tolerance and can be grown in areas where one sees temperatures well below freezing. Most palm experts would say that certain species of Trachycarpus are the second most cold tolerant of any palms, second only to the Needle Palm, Rhapidophyllum hystrix. It is not unusual for enthusiasts to grow Trachycarpus fortunei in colder areas such as Washington state, Maryland, or even Long Island in New York. It is also common to see photographs of Trachycarpus plants covered in snow and untouched and undamaged the following Spring. The lower cold tolerance limit of Trachycarpus fortunei is probably about 5 degrees F, or a bit colder. Many other factors such as duration of cold, humidity and the following day’s warmth affect the limit of cold tolerance.

Palm enthusiasts are always search for the “most cold hardy” of the Trachycarpus. With the introduction of more species in the last decade, there is always an argument about which species is the cold hardy winner. At this point, I’d recommend Trachycarpus fortunei, wagnerianus and perhaps T. takil, but some of the dwarf species might also prove to be equally hardy. Declaring that a given plant has a certain degree of cold hardiness is complicated by the fact that, in domestic planting, sometimes one is not sure which species he truly has. However, over time in the next decade or two, we’ll know a lot more about which species can take the most cold.

SUN TOLERANCE

In general, Trachycarpus like full sun. Also, most can tolerate high heat. Along coastal areas, most species in this group demand full sun. Species planted in shade tend to stall and not do well. Trachycarpus wagnerianus will die if it gets shaded out along the coast. In hot and arid desert areas, some protection from the sun may be required for optimal growth. This varies with which species one is growing. Given correct sun exposure, it is not difficult for Trachycarpus to tolerate temperatures well above 100 degrees F. Thus, one can see how, as a genus, they tolerate a very long thermometer and may be the ideal species for landscape in colder or hot areas. Growing this genus in the most humid of tropical areas may result in rot or fungal problems.

WATER REQUIREMENTS

As a group, Trachycarpus do not have overly high water demands but will tolerate and respond if given ample water. Remember, as a group, they come from mountainous areas where rainfall is more plentiful. Even with this said, some can actually tolerate almost xerophytic conditions with minimal watering and drought periods. Good drainage is preferred and Trachycarpus do not like sitting in a wet bog. Continual watering of the crown of the tree might lead to crown rot. In Southern California, watering once or twice a week is usually adequate. If you are trying Trachycarpus in filtered light, I’d recommend giving them less water as the combination of shade and too much water might result in rot. In desert areas, more water is needed and, as mentioned above, less than full intense sun for optimal appearance of the leaves. If you want general advice, figure three waterings a week when you get very hot and once a week during the winter.

SOIL REQUIREMENTS

As a genus, Trachycarpus are tolerant of many different soil types. They can be grown in rich organic soil, clay and sandy soils. Drainage is important. In general, Trachycarpus do not like to sit in wet, boggy soil. Remember, their natural growing conditions is on hillsides where drainage is good. They are not a “swamp palm”. If one has extremely sandy or gravely soil, organic amendments such as wood shavings or mulch can be mixed into the native soil.

WIND TOLERANCE

Although general air circulation is a good thing for this genus, high winds are known to tatter the leaves of Trachycarpus. They can become unsightly. Therefore, they look better in a wind protected area if you experience a lot of high winds. Species with stiff, hard leaves such as Trachycarpus wagnerianus tolerate windy locations better than the soft leaf species. Mention should also be made about seaside locations where salty, moist breezes can land on the leaves. It is known that such conditions, if extreme, can lead to poor growth and browning of the leaves.

GROWTH RATES OF TRACHYCARPUS

In general, growth of Trachycarpus other than the dwarf species is felt to be at a medium rate. They are not fast growing, but there are scores of other types of palms that are much slower. In most areas, a planted 15 gallon specimen in the garden can have five to ten feet of trunk in a decade. As a genus, the slowest growth rates are seen with small seedlings or plants. It can take from five to seven years to germinate a seeds and get a nice 15 gallon plant. So, if you are the impatient type, start with a good 5g or 15g plant. Trachycarpus fortunei seems to be one of the quickest growers of the family. Once through its juvenile growth stage, rate of growth accelerates. In the ground, growth is faster compared to containerized culture. Trachycarpus wagnerianus is much slower and it may take decades to get a plant with significant trunk. Please note that good culture with adequate water and fertilizer does speed up growth rates. Below I’m showing a photo of the trunk girth of a 5g versus a 15g plant. The former took me about 3 years to grow. It took another 2 to 3 years to produce the 15 gallon size.

FERTILIZER

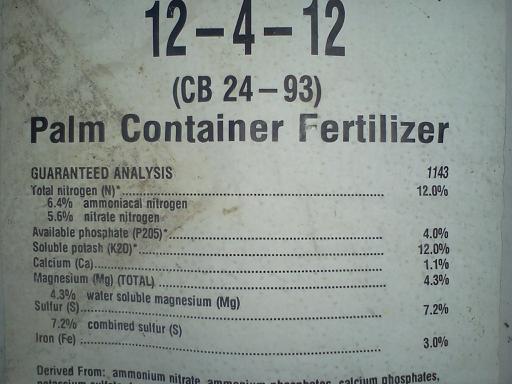

As a genus, Trachycarpus seem to have no special needs or demands compared to other types of palms. We’d recommend using a slow release fertilizer with an N/P/K ratio of 3:1:2 or 3:1:3. Thus, a formulae of 15:5:15 or 12:4:8 would be adequate. Select a preparation that contains microelements and is preferably a slow release formulae. Always follow the directions. If you use a quick release, never fertilize on dry ground. Heavy “pre-watering” a day or two beforehand is required if you use the cheaper, quick release fertilizers.

The pictures below show fertilizers with the N/P/K ratio (Nitrogen/Phosphate/Potassium or Potash) ratio of 12:4:12. These should be fine for Trachycarpus. But, get slow release and one that has a good array of microelements like calcium, magnesium, iron, etc. Their content is also listed on the outside of the bag.

PRUNING

When we discuss pruning, we must be specific about what we are pruning from the tree. Most commonly this would refer to the leaves that have come to look bad. As Trachycarpus leaves age, they turn brown and crisp appearing. They are no longer attractive. As they die, these leaves hang in a downward direction. As mentioned above, most specimens do not retain a petticoat of dead leaves. Over time, these dead leaves will fall to the ground on their own. But, most people prefer to remove them when they become ugly. This is simply done by cutting the leaf stem as close to the trunk as you can. It is a very quick procedure to do this, only limited by easily reaching up to the leaf bases. It is near impossible to hurt the tree when pruning, but don’t overdo it and cut off good looking green leaves. You can also cut off old dead blossoms next to the trunk. It will not hurt the tree. If leaflets are showing brown-tipping, these can also be given a “haircut” by using office scissors to cut off the brown ends of the leaflets.

Pruning or cleaning the trunk is another issue. It is much more difficult. As mentioned above, there is a thinner woody trunk below the fibrous and hairy covering. This covering does age and fall off over many years. And, it starts to fall off at the bottom first. If one wishes to remove it prematurely, this can be done. But care must be taken not to dig into or scar the woody trunk below. It takes a long time to make a little progress. Because of these reasons, I recommend just leaving it alone and letting Mother Nature take her course.

COLD PROTECTION OF TRACHYCARPUS PALMS

Many enthusiast around the world live in colder areas and want to grow some palm trees. Trachycarpus are one of the more cold tolerant of palm species and may be the ideal plant for such growers. As mentioned above, the lower cold limits of Trachycarpus fortunei is somewhere between zero and ten degrees F. Thus, if one’s weather is not going to get to 15 degrees F or lower., probably no cold protection is needed. Below this number, it is probably wise to consider protecting your plant(s). Cold damage comes quickly, even with just one night’s exposure. And, the exact low can never be precisely known in advance. If you think you’ll be seeing temperatures in the single digits or lower, you should plan ahead and protect your plants.

Some people wrap the trunk and crown of leaves with material such as Bubble Wrap or Frost Cloth. Others merely use multiple layers of burlap. Wrapping alone will give some degree of protection. Low wattage Christmas Tree lights or heating cables can even be used inside the wrapping. This gives much more cold protection and is considered essential by some protecting their palms from cold. Nearby heat lamps or lights may help as well. A very ingenious technique I’ve heard of is to build a chicken wire cage around the trunk and crown. Then, from above when it is bitter cold, one drops into the cage pre-collected leaves. This essentially “hides” the plant inside of a stack of leaves. When the cold passes, the cage is released and the leaves cleaned up. Even without cold protection, specimens of the Windmill Palm are known to occur in areas such as Washington State, Scotland and Switzerland. This promotes enthusiasm among people living in colder areas. Successful growth is all a matter of your lowest winter temperatures and what temperature the palm actually experiences. Our best advice is to plan ahead and know your coldest temperatures.

Below are some photographs that were donated by an enthusiast who lives in a very cold part of interior Florida. He not only wraps his plants, but applies low voltage heating cables to the trunk and upper crown. This technique is obviously limited by the height of the plant. You can see the finished job and photos of the cables around the trunk. In his area, Trachycarpus don’t need protecting, but the photos here demonstrate the technique that can be used.

GERMINATION OF TRACHYCARPUS SEEDS

Trachycarpus are dioecious, which means that you need both a male tree and a female to get fertile seeds. Hybridization can easily occur when different species are in proximity. Seeds should be collected when they are mature. Green seeds usually give poor germination rates. Ripe seeds are typically black in color and fall from the blossom easily. Before attempting to germinate the seeds, clean off all the fruit from the inner seed. Scrub the seeds in water to remove remnants of fruit. If seeds were purchased, soaking them in clean water overnight is advisable. Pot up seeds in a well-draining germination mix. We utilize perlite and peat moss, usually at a ratio of three perlite to one peat moss. Place the seeds a bit under the surface of the mix. Water ever two to three days. You don’t want to keep the seeds overly damp but also don’t want them to desiccate from under-watering. Bottom heat or greenhouse germination is not needed unless your weather is cold. Germination of seeds can be challenging. Times to germination range from three to twelve months, depending on the species. An overall germination rate of 25% would be considered very good. Fresh seeds improve germination rates. Divide and pot up new seedlings when they reach the two to three leaf stage.

USAGE OF TRACHYCARPUS IN THE LANDSCAPE

Trachycarpus species are used worldwide in many different types of landscape. Although not commonly used, people who know and appreciate palms utilize this species where they want a single trunk fan palm that doesn’t get too large and is easy to grow. The crowns of leaves are fairly small, so it is easy to put Trachycarpus close to buildings or walkways. Species can be planted as a single specimen or in small colonies or groups. Three plants together in the same area is very attractive. Because of their small trunks and crown size, planting Trachycarpus in parkways next to the street can provide an ideal species. (see photos) Trachycarpus may be the perfect selection for someone who wants a smaller palm for a small yard and full sun. If part of a palm garden, make sure that Trachycarpus don’t get totally shaded out. They like sun. Because of the lack of spines, this genus is good around a pool where one prefers to limit creation of shade and have a species safe for children.

This genus is also an ideal choice for retail stores, commercial projects and shopping centers. They are a fairly low maintenance palm and aren’t to threatening to passer-by’s. Species with stiff leaves (T. wagnerianus) should be planted such that the leaves are not protruding into walkways. If one doesn’t want seeds to fall, young flowers can easily be removed to prevent fruiting and dropping of the round seeds. Interior malls can utilize Trachycarpus if there is adequate air movement and sun. If one chooses to grow Windmill palms inside one’s home, make sure there is adequate sunlight. Shaded out plants do not do well. Inadequate light or the loss of light exposure from surrounding plants is a common cause of decline of this genus.

TYPES OF WINDMILL PALMS – DIFFERENT SPECIES OF TRACHYCARPUS

OPENING COMMENTS: NEW SPECIES OF TRACHYCARUS AND NAME CHANGES

Thirty years ago we palm enthusiasts thought we knew everything there was to know about this genus. We were wrong. In the late 1980’s and 1990’s, two horticulturists from the UK and Germany paired up and started studying Trachycarpus in depth. They visited habitats in Asia. That was the beginning of an introduction of many newly discovered species from habitat. This work was done by Martin Gibbons and Tobias Spanner, both members of the International Palm Society. But, with their discoveries and descriptions. those using old descriptions have gone through the pains of confusion about the species. These folks had to work out in their minds the names of species they already had and comprehend the new species becoming available. Even recently, new species or varieties from different locations are being described. And, nurserymen have often stuck to names from the past. This has caused difficulties as enthusiasts search out species that are not only rare but essentially not in cultivation. Add to this plants that seem to be natural hybrids and species of unclear origin or name and one is left with a confusion about what to call his plant. It is quite amazing how recent discoveries have spurned interest of those collectors in cold areas. With the direction of Gibbons and Spanner, old misidentifications have fallen to the wayside and new species have emerged. For an extensive discussion of their findings and the most up to date species information on this genus, I would invite the reader to view their publications. Descriptions below deal with the major species in cultivation with brief discussions. I have also added a few interesting or unique species that are difficult to locate. I thank my contributors worldwide who have donated photographs for this article. I am adding common names where available (reference from Gibbons/Spanner).

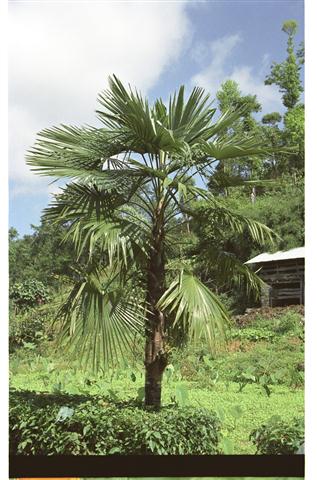

TRACHYCARPUS FORTUNEI (The Chinese Windmill Palm, The Chusan Palm)

Trachyarpus fortunei is the most commonly available and commonly grown of the Windmill Palms. It is of Chinese origin . It is referred to as the Chinese Windmill Palm, the Windmill Palm, or the Chusan Palm. Note how the term “Windmill Palm” can refer to this particular species or to the genus as a whole. In present time this species is being grown worldwide in a whole variety of environments. It is not uncommon to see it growing in colder areas of the United States, southern Europe, the Mediterranean and southern portions of Australia and Africa.

Most specimens one will see are in the height range of ten to twenty feet. However, the oldest of trees may reach forty feet height. The actual trunk diameter is typically six to ten inches. Without the fibrous wrapping, the trunk is thinner. So, as one looks at a specimen Windmill Palm, the trunk is deceptively thicker appearing than the trunk actually is. Depending on the dedication of a person doing the pruning, it can occur that there remains a small portion of the woody petiole protruding from the fibrous trunk. Over time, one can cut and tidy up the appearance of this trunk such that all that is seen is a fibrous trunk. And, eventually even this debris will fall from the trunk and reveal a thinner woody trunk.

The leaves are typically about three feet in diameter and have variable division of the segments. Sometimes this is almost to the point of petiole attachment and on other specimens the division only goes half way to the central point. Leaves are green on the upper side and below, but it is not uncommon for one can see a bit of blue discoloration to the underside of the leaf. Distal leaf segments can flex downward toward the ground. This is likewise variable. Petiole length varies from two to four feet, sometimes dependent on sun exposure.

TRACHYCARPUS WAGNERIANUS ( The Miniature Chusan Palm, the “Waggie” )

This popular species of Windmill Palm is known for its small and stiff leaves. Although not the smallest species of the genus, it is known as a smaller tree because of its extremely slow growth rate. It is not unusual to see a ten year old plant with two, possibly three feet of trunk. The exact origin of this species is unknown as no identifiable colonies are known in the wild. By reports, the first recognition of this species was in Japan. It is occasionally seen in private and botanical gardens. In the past, many felt that this species was the prettiest of the genus. Be aware that, in the nursery trade, this species was previously known as “Trachycarpus takil”, but this name has been given to a more recently described species (see below). I mention this because some old collectors will still refer to it by this old nurseryman’s name.

The leaves are smaller than T. fortunei, typically being two to three feet in diameter when mature. Smaller plants are known to have very small leaves, no bigger than a dinner plant. (see photos below) The leaves, especially on younger plants, are very stiff and the leaflets stick straight out from the center. Also, on younger plants the leaves are nearly a full circle of leaflets. As the plant grows, this may convert to a hemispherical arrangement of the leaflets. This species does have a noticeable petiole with the leaves reaching away from the trunk. The leaflets are induplicate and green in color, often with a gray color underneath. Trunks maintain a hairy, fibrous character until very old. This is especially apparent on young plants. (see photo above under “Trunk” section)

Culture in most coastal areas is in full sun in good draining soil. Hot desert climates may require a bit of protection from full day sun. Cold tolerance is similar to Trachycarpus fortunei; somewhere between zero and fifteen degrees F. If you grow this species in an area that shades out over time, most likely it will die. As mentioned above, growth is slow and availability of this species is sparse.

TRACHYCARPUS MARTIANUS (Common Names After Habitat Localities)

This high elevation species comes from India, Nepal and parts of the Thai peninsula. There are at least three distinct forms of this species, all named according to their locality. In general, it is a medium sized Trachycarpus getting to a height of about twenty feet with a six to twelve inch thick trunk. The leaves are three to four feet across with a three foot petiole. The underside of the leaves is gray and the upper side green. The hallmark and easiest way to spot this species is to look for this white, wooly substance on the leaf stems. A photograph below demonstrates this fluffy substance. The leaves tend to be stiff appearing and are typically half of a full circle in appearance, sometimes more than half. The overall crown appearance is more open than T. fortunei. Growth rate is average. They do like sun. However, cold tolerance is less than the two species above. The lower limit of this species is the lower twenties F., perhaps a bit colder. If cold hardiness is your main concern, then other species would be better for you. This species is fairly difficult to find. It grows quite well in Southern California.

TRACHYCARPUS TAKIL (The Kumaon Palm)

This species comes from a very high mountainous area of northern India. It grows at elevations above 7000 feet and sees bitterly cold winters. Because of its native habitat, it has been touted and hoped by many to be the most cold hardy of the species of this genus. It certainly can tolerate temperatures below 15 degrees F., but its lowest tolerance is still being determined. In appearance, it is similar to Trachycarpus fortunei. On mature trees and compared to the common Windmill Palm, however, it is taller with a thicker trunk, has a bigger crown of leaves with more actual leaves in the crown and larger individual leaves. The leaves are also more stiff than the fortunei. The trunk tends to lose its fibers more readily, giving it a cleaner appearing trunk. A field note for distinguishing this species is that the hastula (a flap of tissue at the junction of the leaf stem with the palmate leaf) is twisted and askew. Fortunei are not this way. Growers also comment on how the trunk of containerized plants is a bit more tidy with prominent hairs.

Because of its natural habitat, this species may be the most cold hardy of all the Windmills. However, in contrast, it might not be as good for areas that see both summer heat and winter cold. I have found it to be a vigorous grower, medium speed. Mention should be made that batches of seeds have been distributed by seed merchants that later were found not to be the true species described above. So, this is an example of how things in the world of Windmills are still in a state of flux.

TRACHYCARPUS OREOPHILUS ( The Thai Mountain Fan Palm)

This species was discovered by the above mentioned Tobias and Spanner is northwestern Thailand over a decade ago. It comes from high elevation mountainous areas where it tends to be humid and moist. Often plants are kept moist with cloud covers and mist. It is a very attractive species with near circular leaves on some plants. The leaves are stiff and green in color with some gray discoloration below. This species gets to about thirty feet of height and has a rather that measures about six inches. The trunk tends to bare itself and not show fiber and hairs. Leaves are about three feet wide and crowns are compact. It has been reported that there are very small teeth on the petioles. Because of its locality, it is felt that this species will like organic, quick draining soil. Cold tolerance is yet to be determined. This species is very difficult to locate. On the first photo below, note how the stiff leaflets make a near 360 circle of leaflets.

TRACHYCARPUS PRINCEPS (The Stone Gate Palm)

This is a very sought-after species of Trachycarpus because of the prominent blue color on the leaves. It is from China and discovered about 15 years ago by Gibbons and Spanner. It comes from an elevation of approximately five to six thousand feet. Trunk height gets to about thirty feet and is covered by a fibrous brown material. But, it is the leaves that make this such a sought-after species. One of the most sought after varieties is from an area in China called “Stone Gate” and has almost white discoloration to the backs of the leaves. So, when one looks up at this tree, the silver-blue color is very obvious. There are also tiny teeth on the petioles. The leaves are about four feet wide on two to three foot petioles. Young plants may not show the blue color to the underside of the leaves when juvenile. However, sometimes it does appear on small plants. Seeds are very difficult to obtain from habitat so consequently plants are extremely expensive.

Photographs below depict the natural habitat of the Stone Gate variety of this species. The first three are from Ruud M., Golden Lotus, Thailand. You can see that this species is living on this near vertical cliff in habitat. Three domestic plants are shown, one in a container and the other two in garden environments. The last photo is from habitat and provided by Gibbons/Spanner. Note how even the tops of the leaves show some of the blue color.

TRACHYCARPUS LATISECTUS (The Windamere Palm)

This species from high elevation areas in India is most known for the fact that it’s leaf segments are wider than other species. There are two varieties. It is a tall species, up to forty feet, with a narrow trunk of six to eight inches. Its leaves are green with a bit of glaucous color beneath. For this genus, the leaves are wide, sometimes up to five feet with wide segments that are divided about half way into the leaf. The petioles are about three feet long and the leaf shape is semicircular or near totally circular. There is a hope that this species tolerates more heat. Cold tolerance is yet to be determined. We’re suspicious it is not as cold tolerant as other species. It is extremely rare in cultivation with few photos available of the native population. Both photographs below are of domestic plants, the first showing Martin Gibbons in the U.K.

TRACHYCARPUS NANUS (The Yunnan Dwarf Palm)

The derivation for the species name is “small” or “dwarf”, so one would anticipate this is a small species and that it is. It comes from high elevation in Southern China. It is small in all aspects. It has a subterranean trunk that only gets a foot or two tall, has small leaves about 2 feet across, and has a one foot petiole that is minimally armed with small teeth. The leaves are fairly divided with segments over half way through the leaf and the leaf color is green with hints of blue. Both this species and T. latisectus above have been recently described by Gibbons and Tobias. It is rare in cultivation. I’ve found this species to be somewhat difficult to grow.

TRACHYCARPUS GEMINISECTUS (Eight Peaks Fan Palm)

This is a dwarf species of Trachycarpus that was described in 2003 and is most closely related to T. nanus. Its habitat is on the border of China and Viet Nam. It comes from a mountainous area at an high elevation. It is unique in that it has a short trunk, usually under five feet and has grouping of the leaflets. The leaf has two, sometimes three leaflets in close proximity. This gives it a unique appearance. The leaves are green on top, silver below and very thick to the touch. The photograph below by Martin Gibbons and Tobias Spanner demonstrate the different appearance of this palm. The close up of the leaf shows the grouping of the leaflets. It should prove to be very cold hardy but is almost unknown in the nursery trade at this time.

OTHER SPECIES

I am making this category because it is my feeling that new species will be added over time. There are known to be more than one variety of several of the species above. If taxonomists agree that new species exist, I will amend this article and add them over time.

CONCLUSION

The term “Windmill Palm” refers not only to a particular Trachycarpus species but also to the genus as a whole. Individual common names have appeared over time to distinguish the different species. As a group, none of the species is overly large. The tallest get to about forty feet and some are dwarfs, not over three feet tall. All are single trunk and most have a fibrous material covering a thinner woody trunk within. As a group, Trachycarpus are a very cold tolerant genus. Experience over time will let us know the most cold tolerant species, but there are definitely species that will tolerate temperatures down to close to zero F. Interest in the Windmill palms has increased in recent years. It makes an ideal palm for small gardens, patio plantings, parkways, and commercial projects. These plants look nice planted together as a group of several plants or as a small colony. It is a low maintenance palm that is fairly easy to grow and not too water demanding. In general, all species prefer sun and good drainage. Because of its versatility and smaller size, , it is quite surprising that we don’t see Trachycarpus planted more widely in communities. Rather, we see scores of Washingtonia (Mexican Fan Palms) in Southern California and very few Trachycarpus. My suspicion is that this is because people just don’t know about this interesting and attractive genus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

I wish to thank the individuals below for their contributions and allowing me to use their photographs for this article.

Ruud Meeldijk, Golden Lotus, Thailand

Martin Gibbons, Palm Centre, U.K.

Tobias Spanner, RarePalmSeeds, Germany

Rick Penman, Southern California

C.W., Southern California

Mathew Boozer, South Carolina

Walter Darnall, Lake Placid, FL

Tom Woodruff, Salem, Oregon

Thank you for reading this article. Feedback always appreciated. Check elsewhere at this site for over 4000 photographs and 50 articles on palms and cycads.

Phil Bergman

Owner

- PALM TREES, CYCADS & TROPICAL PLANT BLOG - October 1, 2020

- TRACHYCARPUS

The Windmill Palm - September 30, 2020 - FAN PALMS –

PALMS WITH CIRCULAR LEAVES - September 29, 2020